TL;DR (Summary)

Three improvements to current watermarking methods for LLMs:

- (1) theoretically grounded and empirically validated statistical tests that guarantee false positive rates,

- (2) evaluation on classical NLP benchmarks,

- (3) extension to scalable multi-bit watermarking

Links

Technical Background

How do current methods watermark LLM’s outputs?

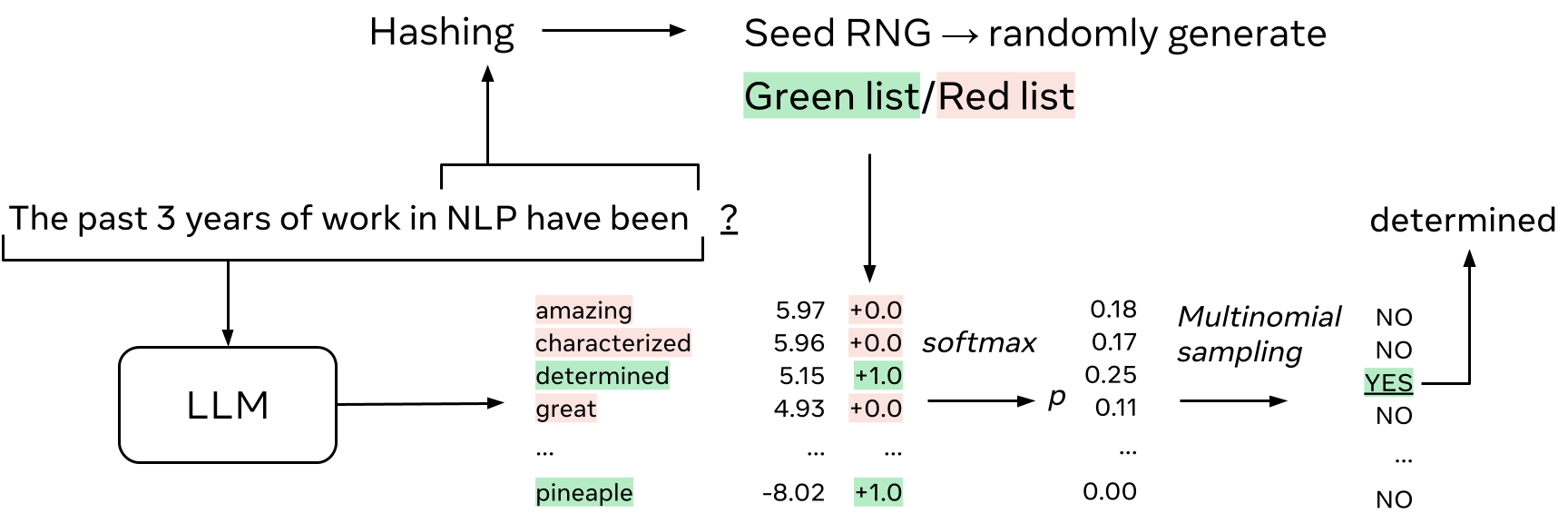

Generation

Most often, LLMs take as input the context and output a vector \(l\in \mathbb{R}^{V}\) of logits, tranformed into \(p=\text{softmax}(l) \in [0,1]^{V}\) representing the probability of each token in the vocabulary being the next. To generate a sequence from a context, we usually sample a token from distribution \(\mathbb{P} \left( . \big| x^{(-N_p)},\dots, x^{(-1)} \right)\) with some variations (top-k sampling, nucleus-sampling, beam-search, etc.) then append it to the context and repeat the process.

In the case of watermarked generation, the sampling is altered to embed the watermark. In many cases (e.g. [1,2]), this is done by hashing \(h\) tokens before the token to generate, using this to seed a random number generator (RNG), and modify the sampling using the RNG’s output. For instance, [1] uses the RNG to randomly generate a set of greenlist tokens, and biases the logits to favor these tokens.

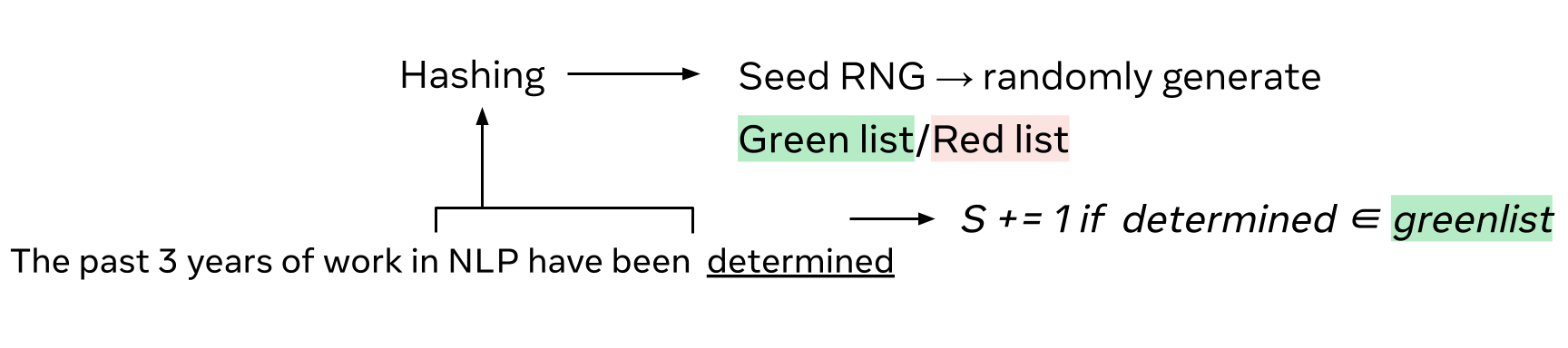

Detection

At detection time, we do the same process again, ie hash \(h\) tokens, use this to seed a RNG, then use the RNG’s output to score the token that follows. To take the same example as above, [1] uses the RNG to re-generate a set of greenlist tokens, and scores the token that follows. If the token is in the greenlist, the score is 1, otherwise it is 0.

\(Z\)-scores

The detection tests the hypothesis \(\mathcal H_0\): “the text is natural” (human written or written without watermark), against \(\mathcal H_1\): “the text has been generated with watermark”.

Current approaches [1,2] approximate the underlying distribution of the score \(S_T\) by using a \(Z\)-test. This statistical hypothesis test determines whether a sample mean differs significantly from its expectation when the standard deviation is known. It computes the so-called \(Z\) statistics:

\[Z = \frac{S_T/T - \mu_0}{\sigma_0 / \sqrt{T}},\]where \(\mu_0\) and \(\sigma_0\) are the expectation and standard deviation per token under the null hypothesis \(\mathcal H_0\), i.e. when the analyzed text is not watermarked. The \(Z\)-test is typically used for large sample sizes assuming a normal distribution under the null hypothesis thanks to the central limit theorem. This assumption is key for computing the p-value: the probability of observing a value of \(Z\) at least as extreme as the one observed \(z\), under the null hypothesis:

\[\text{p-value}(z) = \mathbb P (Z>z | \mathcal H_0) = 1 - \Phi(z),\]where \(\Phi\) is the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution. At detection time, we fix a false positive rate (FPR) and flag the text as watermarked if p-value(\(z\)) \(<\) FPR.

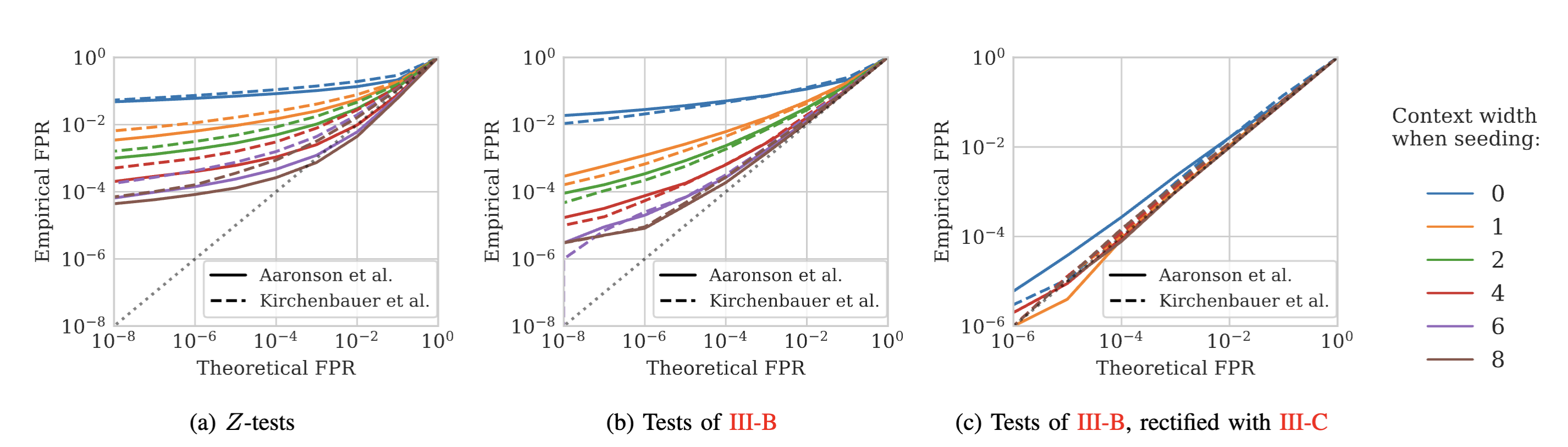

🧱 What’s wrong with \(Z\)-scores?

The \(Z\)-tests approximate the underlying distribution of the scores. In practice, we observed that assumptions are not met, and the resulting p-values are not reliable.

For instance, if we run detection on 100k natural text samples taken from wikipedia, with 10 different watermark keys (1M detection samples in total), we observe that the p-values are not uniformly distributed (as expected under the null hypothesis) and that we largely under-estimate the false positive rate (FPR).

This is solved with more rigorous statistical tests, that do not rely on the normality assumption, and by scoring only some tokens to remove repetitions. With these improvements, the empirical FPR matches the theoretical FPR.

🧱 How should we evaluate text quality in watermarking?

The quality of the watermarked text is a key aspect of watermarking. It should not be too different from naturally generated text, otherwise the watermark would be too easy to detect and might decrease the utility of the model.

Most of the time, the quality is evaluated by perplexity, a metric that measures how well a language model predicts a sample of text, or in this context, how likely was the watermarked text. On the other hand, LLMs are evaluated on downstream tasks, such as question answering, math solving, etc. We argue that the quality of the watermarked text should be evaluated on these tasks as well, as it is the ultimate goal of LLMs. We explore this idea by evaluating the quality of a watermarked LLM on classical NLP benchmarks (see Tab. I of the paper).

🧱 How to easily extend these methods to multi-bit watermarks?

In zero-bit watermarking we know the key used to generate the watermarked text, and we want to detect if the text has been generated with this key or not. In multi-bit watermarking, we try to decode a message from the text, without knowing the key used to generate it.

It is rather easy to turn a zero-bit watermarking scheme into multi-bit watermarking, by associating a secret key per message. However, in our case, this would require re-generating the secret vectors for each possible key, and score the text with each of them.

We introduce in the paper a simple way to scale previous methods to multi-bit watermarks, based on the idea of using a single secret vector and shifted secret vectors for each message.

References

[1] John Kirchenbauer, Jonas Geiping, Yuxin Wen, Jonathan Katz, Ian Miers, and Tom Goldstein. A watermark for large language models. ICML, 2023.

[2] Scott Aaronson and Hendrik Kirchner. Watermarking GPT outputs, 2023. URL https://www.scottaaronson.com/talks/watermark.ppt